Evictions in Ireland – How Your Ancestors Fought Back

Now, you might think it would be wonderful to have a surname that enters into the English language based on your deeds and is used by millions of people. Then again, your name might be Captain Charles Boycott. I think you might see where this is going!

In today’s letter we will look at how his surname, Boycott, came to enter the English language as signifying an act of civil disobedience during his time in Ireland.

Charles Boycott arrives in Ireland.

Charles Boycott was born in Norfolk in England in 1832. He lived in England until 1850 when his family bought him a commission in the British army. He was transferred to Ireland with the 39th Regiment of the Foot, where he served until 1853, when illness forced him to sell on his commission. He must have enjoyed his time in Ireland and clearly saw opportunity as he leased a farm in County Tipperary.

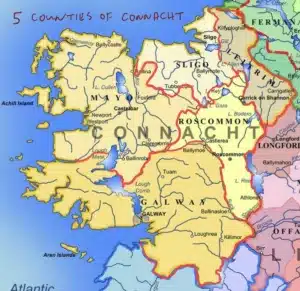

He remained in Tipperary for a short time before purchasing land on Achill island in County Mayo in 1854 (if you have seen the movie “The Banshees of Inisheerin” you have some idea of the scenery he had to “tolerate” on a daily basis). He settled there with his wife, built a house and started to make a go of farming. Evidently, Boycott had skipped his time in charm school as he was frequently in dispute with both the local tenants and administrators during this time.

One of the largest land-owners in County Mayo, Lord Erne, must have been impressed with Boycott’s ability to persist through these disputes. He offered Boycott the job of Land Agent for his estate of 1,500 acres near Lough Mask outside the town of Balinrobe in Mayo. Boycott accepted the job which included collecting rents for a personal fee of 10% from tenant farmers on the estate.

Unfortunately, Boycott’s temperament accompanied him to Lough Mask – it wasn’t long before he started to annoy tenants by removing small rights that had been in place for decades as well as closing down rights of way. In 1880 events on Boycott’s estate were about to become a focus for the tenant rights movement that was growing all over the west of Ireland.

A Growing Dissatisfaction across the land.

Agriculture was by far the largest economic activity on the island of Ireland during the late 1800s, but almost all farmers were tenants to about 10,000 landlords – many of whom were absentee and living in England and Scotland. A smaller group of the landlords – about 750 – owned over half the island of Ireland between them.

These tenant farmers typically farmed between 10 and 50 acres but still only held year-to-year leases and could be evicted without reason at any time. In addition, a further large group of people were farm labourers who relied on these tenant farmers and the larger farms for a living. They had no rights whatsoever.

Movements to address this lack of fairness started to emerge after the Great Famine of the mid 1840s, but they really started to gain momentum in 1879 with the founding of “The Irish National Land League”.

The Land League was very active in County Mayo and started to stage rallies and protests focused on the unfairness of evictions in Ireland. The movement had rejected the idea of violence to protest evictions and adopted a policy that was proposed by Charles Stuart Parnell, an Irish reform leader of the time. In Parnell’s words:

“When a man takes a farm from which another has been evicted, you must shun him on the roadside when you meet him – you must shun him in the streets of the town – you must shun him in the shop – you must shun him on the fair green and in the market place, and even in the place of worship, by leaving him alone, by putting him in moral Coventry.”

Evictions in Ireland – How Your Ancestors Fought Back.

The harvest was poor across County Mayo in 1880 and Lord Erne agreed to a 10% reduction in rent. However, the tenants of Erne’s estate were emboldened by the recent Land reform movements and saw an opportunity. They demanded a 25% reduction in rent – and this was refused. Boycott then issued demands for the rent and eviction notices against twelve of his tenants.

However, the local tenants were pre-warned and mobilised. Many tenants refused to accept the eviction notices and drove the eviction servers off the land. The situation escalated quickly with many activists in the area arriving at the estate to encourage the labourers and trades people there to walk off their jobs. All of Boycott’s employees quit their work eventually putting him in a position of gathering the harvest and managing the estate without labour. Shopkeepers and provision stores in Ballinrobe also stopped providing Boycott and the estate.

Boycott now had a harvest of crops worth about £500 – but no one to harvest them. This affair caught the attention of newspapers across the United Kingdom who saw it as a case-study on the wider dissension brewing across Ireland. In fact, the verb “to Boycott” made its first appearance in The Illustrated London News – where it described how “To Boycott” has come to mean “to intimidate”, to “send to Coventry” or to “taboo”.

A “Boycott Relief Fund” was established in Belfast in November, 1880 – but his harvest that had a value of £500 cost £10,000 to save. By this point, Captain Boycotts continued residence in the area was (ironically) untenable and he self-evicted himself and his family at first to Dublin and then onwards to England by the end of the year.

A Change for the Better.

The Boycott affair – and its subsequent reporting in newspapers – strengthened the hand of tenant farmers all over the island. There were reports of “boycotting” all over Ireland which forced the government of the day to consider serious land reform.

April 1881 saw the introduction of the ”Land Law Act” and the establishment of the Irish Land Commission which fixed rents for 15 years and gave a fixity of tenure to tenant farmers. Further land reform acts were introduced in Ireland over the following decades and by 1907 the majority of tenants had the opportunity to purchase their land under favourable terms. As a result, you see a huge shift in land ownership from the landlord class to small farmers between the 1890s and 1920s. To this day, Ireland has one of the largest percentage of farmer-owned farms in the world – much higher than that found in the United Kingdom.

Over the next number of years Captain Boycott adopted the use of his alternative surname of Cunningham when travelling in Ireland and to the USA. Funny enough, although he settled as a land agent in Suffolk in England, he often returned to Ireland for holidays and did not seem to hold the country to blame for being swept up by a massive wave of change in such a personal way.

How about you – were any of your Irish ancestors tenant farmers in Ireland? Have you ever heard stories of evictions in Ireland and civil unrest like the ones I share above?

That’s the end of our letter for today. As always, do comment below if you would like to share the surnames in your Irish family tree or even a story or two!

Slán until next week,

Mike.

Only Plus Members can comment - Join Now

If you already have an account sign in here.